Started: December 13, 2017

Finished: February 10, 2021 (...yeah, I know. Quite the time gap here. See below for the full accounting).

Why I Read This Book / My History with This Book

So, this is one of those classic books that everyone knows about (even if not everyone has actually read it.) Everyone at least knows about Don Quixote fighting the windmills.

As far as memory serves, my first encounter with this book was when I was about 7, and I was staying over at my grandparents' house, sleeping in my aunt's old room, and was reading through all my aunt's old high school books, in which there was a comic book of Don Quixote which featured him (you guessed it) fighting windmills. You know the story as well as I do--Don Quixote imagined he saw giants, he charged them, only for the giants to turn out to be windmills.

"Well, that's pretty stupid," I thought to myself. "It turned out it was all in his head all along? None of it was real and there are no dramatic stakes? Why in the world would I want to keep reading this book?"

And that remained my attitude throughout the rest of primary school and secondary school. Other classic books intrigued me--for example I was intrigued by the premises of books like The Three Musketeers, The Hunchback of Notre Dame, or War and Peace, etc., long before I was mature enough to read them--but Don Quixote I had little interest in.

My interest picked up slightly (very slightly) in college, when I began to get some idea of the esteem that this book has regarded in. I also began to get slightly curious about what was actually in this book. (How could you fill 800 pages with just a man fighting windmills?) That, plus, as a literature minor in college, I had a vague ambition to try to tackle all of the great books one day. So ever since my college days, this book has been somewhere on my To-Be-Read list, but somewhere near the bottom.

The book jumped up higher on my To-Be-Read list in 2005, when one of my good friends in Gifu Prefecture--a British gentleman who I used to hang out with in the evenings and trade book recommendations with--became very enamored with Don Quixote. He had just finished reading it, and he would often talk about how it was the most beautiful book he had ever read, and for a while afterwards, he was on a quest to find another book which could replicate that feeling. None of my book recommendations seemed to satisfy him. (*1)

This, of course, made me curious to check out Don Quixote for myself someday.

But I truly became interested in this book in 2010 when a friend of mine gave me a copy of The History of World Literature by John L. Voth (from The Great Courses series). I loved the whole series--Voth is an excellent lecturer--he really has a way of making whatever book he is talking about at the moment sound absolutely fascinating. (*2) But I was particularly fascinated by his description of Don Quixote.

Among other things, Voth talks about how Cervantes had a great deal of fun playing around with the identity of the narrator in Don Quixote. The story starts out with the author retelling the chronicles of Don Quixote of La Mancha. But then, right at a climatic moment, right when Don Quixote and his adversary are about to exchange blows with each other, the author claims that the manuscript that he is using to tell this history has abruptly come to an end, and that he doesn't know what happens next. The next chapter then deals with the author's search for the continuation of Don Quixote's story. He claims to stumble upon an Arabic version of Don Quixote's history, written by a Moor, in the market, where it is being sold as scrap paper. But since the author can not speak Arabic, he has to hire a Spanish speaking Moor to translate Don Quixote for him from the Moorish version. Thereafter, there are multiple layers of narration and commentary for the story of Don Quixote--there is the voice of the Arabic historian, the voice of the translator, and the voice of the author. Occasionally the author will doubt the accuracy of the translation, or the translator will interject to say that he doubts the accuracy of the text he is translating, etc, and all these overlapping voices add to the developing story. Doesn't that sound like a lot of fun? (*3)

But then Professor Voth described the sequel to Don Quixote--Don Quixote Part 2. The sequel (which was originally published 10 years after the original) is even more bizarre, because the sequel takes place in a world in which the original Don Quixote is in print and has been read by all of the characters. So Don Quixote is now living in a world in which everyone he meets has now read Don Quixote. Now this was getting really meta! And it sounded just crazy enough that it could be really interesting! Imagine characters in the book who have read the same book that the reader has, and could make comments on it. They could be critics of the book and characters in the book at the same time! (*4) , (*5) , (*6)

So, after hearing all that, I was officially interested in Don Quixote, and was just waiting my chance to get around to it. But when do you ever just settle down and read Don Quixote? I had to wait for a good excuse to pick it up.

That excuse came via the book club I was part of a few years back.

Now, admittedly Don Quixote is not a typical choice for your typical wine-and-cheese book club. But this was a more serious book club (*7). After all, the very first book we read was The Karamazov Brothers by Fyodor Dostoevsky. (And that wasn't even my choice, that was one of Tom's choices.) So, I figured, if we could slog our way through Dostoevsky, we could handle Don Quixote.

Tom, however, (one of the other founding members of the book club), put his foot down on this. He had tried reading Don Quixote once, and there was no way he was giving it another try (*8)

Tom had previously gotten all through way through Part 1 of Don Quixote, but he had given up on Part 2. And he had absolutely no desire to try reading the book again. (*9)

But then, Tom got a new job, and moved to Columbia (*10). The last book club book Tom met with us to discuss was Thank You, Jeeves by P.G. Wodehouse. At the end of that book club discussion, it was time to choose the next book.

"Well, I won't be around for the next book, So I guess you can choose it without me," Tom said.

"Right, I've been waiting a long time for this..." I said.

"Don Quixote?" everyone else said.

"It sounds like it could be a really fun book," I said.

Tom gave us a "Well, it's your funeral" kind of shrug of the shoulders, and the rest of the book club agreed to start Don Quixote.

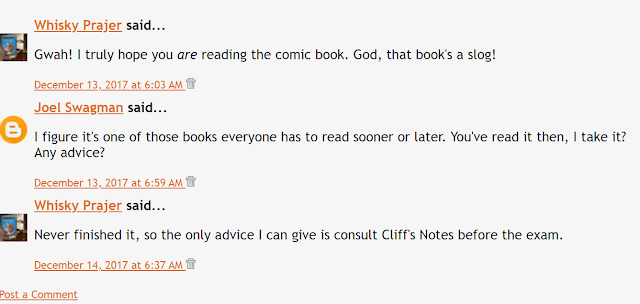

Wordsworth Classics are the editions that are available in Saigon (*11), so that was the edition I picked up. (The version pictured above at the top of the post.) I started reading the book on December 17, 2017, and, for fun (*12) posted the cover from the comic book as my image.

|

|

| http://joelswagman.blogspot.com/2017/12/blog-post_13.html?showComment=1513162988153#c7646107431012169906 |

This was now the second warning that I had that maybe this book wouldn't be quite so fun as I had thought.

In my book club, we agreed to finish Part 1 by February 2018, which in the Wordsworth edition is pages 1 through pages 367. And , although Part 1 was a bit of a slog to get through at points, we actually all made our deadline (*13) and finished Part 1 on time for the meeting. And had a good discussion based around Part 1.

...I suppose I should probably talk about the difference between Part 1 and Part 2, because I don't think this is widely known outside of literature students.

What we know of as Don Quixote is actually two books--there was the original book, published in 1605, and then there was a sequel that was later published in 1615. In other words, this is two books in one.

So, this brings up the question I face - with - all - my - reviews - of - compilation - books: do I review each book separately, or just review the compilation as a whole?

As you can see, I've decided to do this as one big review. Mostly because ever since the 1600s, publishers have treated it as just one single volume, and so I'd be breaking with established modern tradition if I were to treat Part 1 as it's own book.

...but, I kind of wish I would have just reviewed Part 1 back in February 2018, when it was still fresh in my mind. Because our book club actually got through Part 1 alright, and there would have been plenty to talk about for Part 1. Now it's 3 years later and it' all a bit foggy in my mind. (*14)

Anyway, back to 2018...

We decided to give ourselves another month for Part 2, and then meet up to discuss again. But none of us made that deadline, so we pushed it back a bit more. And when none of us made the deadline a second time, we had to admit to ourselves that we weren't going to finish the book, at least not on the deadline. All of us said we planned to continue to finish the book in our own time, but as a book club, we decided to move on to another book (The Martian Chronicles by Ray Bradbury).

It was the first and only book that our book club just gave up on. (And remember, this was a book club that read The Karamazov Brothers.) But I had every intention of finishing the book by myself. After all, no point in slogging all the way through Part 1 only to stop now, right?

And then it took me 3 more years...Yeah, I know. I'm not proud.

To be fair to myself, it was a very busy 3 years. For one thing, in the interval I got married and a had a kid. (And just in case there are any young single people out there who are wondering whether having a two- year-old child running around the apartment increases your leisure reading time, I can safely tell you that no it does not.) I also completed the Delta Module 2 (which was an intense 6 weeks in which I did no pleasure reading), and then spent the next year after that completing the Delta Module 3 (which wasn't quite as intense as Module 2, but which did take over my reading list for the time that I was doing it.) I also moved apartments 3 times, changed jobs and job position a few different times, and for most of the time during the past 3 years was working 60 hour weeks at multiple different jobs. And I was also (on and off) trying to study Vietnamese.

So, yeah, I've been pretty busy.

But the thing that really hampered my progress with Don Quixote was getting distracted by other books. (*15) Actually back in 2017 and 2018, I was involved in 2 different book clubs (*16), so my reading list was already pretty full. But even in addition to that, I still managed to distract myself with other books. I just couldn't bring myself to finish Don Quixote, and found myself reaching for other books to distract me instead. (*17)

The Past 3 Years

So, over the past three years, this book (and my inability to finish it) has been popping up a lot in conversation, at my work, and occasionally in my blog posts. I'll try and run through a few of the highlights here.To start with, my inability to finish this book would become a running joke. Co-workers began commenting on how I was perpetually lugging the book around, and asked if I was ever going to finish it.

As far as I know, none of the other book club members ever finished it either. (I saw one of them a few months back, and I asked him if he had finished Don Quixote. "Don't ask me questions you already know the answer to," he replied.)

In April of 2018, I made a video talking about all the books I was currently reading, and mentioned my struggles to get through Part 2 of Don Quixote. (Watch from 4:20 of the video to see the part about Don Quixote.)

In May of 2018, I pulled the book out of my bag to read at the airport, and my wife said, "You have read that book for a long time." I corrected her grammar --"You have been reading"-- and subsequently this became my favorite example sentence for illustrating the difference between the present perfect and the present perfect continuous. I've had the occasion to use that story often with co-workers when talking about the present perfect continuous, and I even integrated that story into one of my Delta essays.

...and speaking of the Delta, I actually brought Don Quixote with me to Chiang Mai when I did the Delta there. I didn't get much leisure reading done, but I did bring the book into one of the lessons with me as a visual prompt when teaching the difference between the present perfect and the present perfect continuous.

|

| https://docs.google.com/document/d/1gGCNRa03cPxhlgd-MAXkbnouweDRU7RuvHYA0lt5RMk/edit?usp=sharing |

I also got an opportunity to integrate Don Quixote into my teacher training material. During my time in the Teacher Training Department, I had to create a demonstration lesson to illustrate how to teach a lesson on functional language for giving advice. I started the lesson off by showing problems from my life that the new teachers had to give me advice on. The first problem I put on my slideshow was my failure to finish Don Quixote.

It was meant to be somewhat tongue-and-cheek, of course. But even as a joke, it backfired when the trainee teachers refused to accept that this as a problem.

"Wait, why is this a problem?" they asked.

"Because every night I come home, and I see this book sitting half-read on my bookshelf," I said. "And the feeling of having something not completed is eating away at me."

"Then finish it."

"I'm trying, but it's so long and boring."

"Dude, just stop reading the book if you're not enjoying it."

"Well, I would," I said. "But I'm 500 pages into it. I can't stop now. I mean, I've slogged my way through this far, it would be a waste of all that effort to stop now before I finish it."

They were absolutely confounded that I would consider this to be a problem, even in jest. It was a reminder that not everyone thinks the same way I do. (For those of us who studied literature in college, and still feel some obligation to slog our way through the classics, it's a reminder that not everyone else feels this way.)

This past spring, during the Coronavirus lockdowns, I made another go at finishing up the last 300 pages of the book. I also tried to review Part 1 by listening to it the Librivox recording (as I wrote about here).

My daughter, who was 1.5 years old at the time, was becoming more and more interested in the books around the apartment, and would frequently pick up whatever was lying on the floor and cry until someone read it to her. Unable to distinguish between which books were for babies and which ones were for adults, she would frequently pick up Don Quixote when I left it around the apartment and hold it up to me to read it to her. I thought it would be funny to make a video in which we pretended she was upset at how slow my progress was on Don Quixote, and that's why she was holding up the book and crying. I posted it on Facebook at the time and got a laugh from my friends.

She's upset about my lack of progress on Don Quixote

And then after the January 6 insurrection, I started to read a lot about how the insurrectionists who stormed the U.S. capital were living in a fantasy reality, and I thought to myself "Well I'll be! Don Quixote is actually relevant to our political scene." I wrote a brief little blog post about it, mostly to remind myself to talk about this aspect of Don Quixote when I finally got around to the review.

...and now here I am with the review.

The Review

So, if you've read through all of that, you must be thinking that Don Quixote is an absolutely terrible book to get through.But actually, it wasn't the worst thing ever.

It's actually easy to read in the sense that the narrative is straightforward and easy to understand.

I mention this explicitly because there are so many classic books out there that are really difficult to understand. You know what I'm talking about--classic books which are written in archaic English, or written completely in verse, or (moving into the 20th century) all those modernist writers who wrote in an indecipherable of code. As a literature minor in college, I have so many memories of trying to struggle through books I couldn't understand. (Paradise Lost, Dante's Inferno, Beowulf, Canterbury Tales, Spensor's The Fairy Queen, James Joyce, T.S. Eliot, Virginia Woolf, etc, etc, etc).

Don Quixote, by contrast, is completely comprehensible (*18).

But to praise a book for being comprehensible is, of course, setting the bar a bit low. What about asking if it is fun to read? Does the prose flow? Does the writing style suck you in?

Unfortunately, but not surprisingly, the answer is no. Most old books are written in a style that doesn't fully engage modern readers, and Don Quixote is one of them. I don't know if it would have been different if I had had a more modern translation. But in the translation I had, the prose felt dry and old-fashioned. Which is, of course, what you would expect from a book this old.

At a certain village in La Mancha, of which I cannot remember the name, there lived not long ago one of those old-fashioned gentlemen who are never without a lance upon a rack, an old target, a lean horse, and a greyhound. His diet consisted more of beef than mutton; and with minced meat on most nights, lentils on Fridays, griefs and groans on Saturdays, and a pigeon extraordinary on Sundays, he consumed three quarters of his revenue; the rest was laid out in a plush coat, velvet breeches, with slippers of the same, for holidays; and a suit of the very best homespun cloth, which he bestowed on himself for working days. His whole family was a housekeeper something turned of forty, a niece not twenty, and a man that served him in the house and in the field, and could saddle a horse, and handle the pruning hook. The master himself was nigh fifty years of age, of a hale and strong complexion, lean-bodied and thin-faced, an early riser, and a lover of hunting. Some say his surname was Quixada, or Quesada (for authors differ in this particular); however, we may reasonably conjecture he was called Quixana; though this concerns us but little, provided we keep strictly to the truth in every point of this history.See what I mean? Perfectly comprehensible, not at all intimidating, and yet, written in a rather old fashioned dry and stilted style, no?

But on the positive side, the old-fashioned style doesn't impede the humor of this book. And I was pleasantly surprised to find out how funny this book could be at times.

If you're at all familiar with this book through cultural osmosis (and I'm sure you are) then you already know the basic premise for most of the jokes: Don Quixote has read too many fantasy book about heroic knights (what are known as chivalric romances) and so he becomes convinced that he is a heroic knight himself, and the extent of his delusion causes him to imagine everything around him as part of the fantasy. He thinks windmills are giants, he mistakes inns for castle, mistakes prostitutes for princesses, mistakes herds of sheep for armies of soldiers, and mistakes wine skins for the head of a giant.

Now, if you're thinking: "Doesn't that one-note gag get a little tiring after 768 pages?" The answer is "Yeah, sometimes." There were times when I got a little bit sick of Don Quixote and his delusions. (Sorry fans of this book.)

For one thing, the simple act of Don Quixote mistaking one thing for another thing is really only half the joke. Much of the humor comes from the reaction of the other people around him. For example, there's a very comical scene when Don Quixote mistakes a flock of sheep for an enemy army, and he charges the flock of sheep on his horse and starts attacking and slaughtering the sheep. And Don Quixote's companion, Sancho Panza, realizes what is happening and goes into fits, yelling and screaming all sorts of oaths, and pulling at his beard, but it is too late to stop Don Quixote. Meanwhile the shepherds are confused about what is happening, until their initial confusion gives way to anger. It's a great scene of everybody around Don Quixote getting all upset, while Don Quixote is blissfully ensconced in his fantasy world.

The other part of the joke is that after Don Quixote gets humiliated by the reality turning out differently, he always stubbornly refuses to admit he was wrong. So, for example, in the scene above when Don Quixote finally comes to himself and realizes he is surrounded by sheep (after having been attacked by the shepherds), and Sancho is chiding Don Quixote for not having listened, Don Quixote creates elaborate explanations to convince Sancho that he had been right all along. And these conversations between Don Quixote and Sancho Panza are where the real humor of the book comes in, in which Sancho Panza is continual trying to point out what just happened in reality, and Don Quixote is desperately trying to save face by coming up with excuse for what has just happened.

Another source of humor is that sometimes Don Quixote's delusions can set off a whole chain of slapstick that end up affecting multiple people. For example, there's a scene at an inn, in which Don Quixote mistakes one of the prostitutes for a princess, and then the mule driver (who had made an arrangement with the prostitute) attacks Don Quixote. The inn-keeper runs up to see what all the commotion is. The prostitute runs to hide in Sancho's bed, who, terrified by the lump in his bed, starts hitting her. Then the inn-keeper runs in to hit the prostitute while the mule driver hits Sancho. Then the lamp goes out, and a policeman, who is also staying at the inn, thinks someone is getting murdered and then he runs into the room, and then...

...well, you get the idea. The shenanigans just keep continuing.

So the humor is perfectly accessible. Even though I have no doubt that a lot of the satire on Spanish institutions and culture went right over my head.

Speaking of the satire, now is probably as good a time as any for me to note that Don Quixote is to Spanish literature what Shakespeare's plays are to English literature. In other words, the commentary on Don Quixote is enormous. Every incident in the book supposedly has multiple meanings. Everything in the book is some sort of satire on the religious or political institutions of the day. So if you do any research at all, you could easily get lost in the commentary.

But who needs that? The book is already too long as it is. And moreover, you don't need it. I'm sure there were all sorts of layers, satires, and hidden meanings in this book that went right over my head, but you can still enjoy the surface meaning of the story easily enough without aid of commentary. And much of the humor in this book, particularly the slapstick humor, or the scatological humor, needs no commentary to make it accessible.

[I should also make it clear, if it's not already, that I'm a philistine, and am only reviewing Don Quixote from the perspective of readability and enjoyability for the average guy in 2021. Throughout my review, you should assume that any passage I complain about is actually brilliant, and there are volumes of scholarly work devoted to explaining just how brilliant it is, and I was just too dumb to get it.]

Another thing which makes Don Quixote fun to read is the constant satire of chivalric romances (i.e. stories about legendary knights) which were apparently very popular in Cervantes' time.

Don Quixote, and most of the rest of the characters in this book, are intimately familiar with the stories about knights and princesses, and these stories make a frequent topic of conversation in the book. The joke, of course, is that Don Quixote thinks all these stories are true, which results in a lot of humor and a lot of opportunities to satirize these stories. Sometimes Don Quixote will attempt to explain the plot of these stories to Sancho, and Sancho will ask a lot of common-sense-type questions about all the plot holes in the story, which will result in Don Quixote getting frustrated.

Sometimes other characters will argue with Don Quixote about the plots of these books.

And sometimes Don Quixote will attempt to replicate in real life the plot of these books. (Such as when Don Quixote decides that he needs to go into a period of despair and madness in the wilderness because of being lovesick, simply because this is what usually happens to knights in the middle of the chivalric romances.)

In my review of A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court by Mark Twain, I praised Mark Twain for all the humor he was able to get out of satirizing the conventions of the Arthurian legends. But I may have been too generous in crediting Twain's originality. It turns out, Cervantes was already doing this 250 years before Twain.

Interestingly enough, though, the main target of Cervantes' satire is not the Arthurian legends. King Arthur, Lancelot, Merlin and Guinevere do all get mentioned in Don Quixote, but they are not the main focus of Don Quixote's obsession. The main focus is on later books about knight errantry which were apparently more popular on the European continent in Cervantes' day. The foremost of these (the book that gets referenced repeatedly by all characters in Don Quixote) is Amadis of Gaul. (Read all about it on Wikipedia HERE.) Which apparently was massively popular on the Iberian Peninsula in the 16th Century, and which spawned a whole bunch of sequels and spinoffs. (Some of which are also mentioned in Don Quixote, such as Amadis of Greece (W)).

If you're like me--enough of a fantasy nerd to be vaguely interested in all of this stuff, but at the same time intellectually lazy enough that you will probably never read the original 16th century chivalric romances--than Don Quixote can act as the perfect survey course for all of these medieval legends and romances that you never even knew existed. I found it all fascinating. (*20)

But let's talk about the actual plot of the book. (***Spoilers ahead***)

The book starts out with just the humor of Don Quixote mistaking everything for something out of a chivalric romance. But as funny as this is (and as I noted above, Cervantes does do a good job of mining a lot of humor out of this), it can also get repetitive and tiresome after a while.

But the other trick Cervantes uses is to have Don Quixote's wanderings be a way to introduce new people and their stories. Don Quixote encounters a lot of other people on the road, and briefly becomes involved in their stories.

Sometimes Don Quixote will try to help them, in which case he often just makes the situation worse. But more often than not, he will simply be an observer who watches the drama unfold.

In the second half of Part 1, Don Quixote actually does start to take on a sort of over-arching plot, as Don Quixote encounters a man named Cardenio out in the wilderness. Cardenio has a long backstory about his lost love, which Don Quixote and Sancho hear, and then they start travelling with him. They then encounter another lost lover with her own backstory, and pretty soon there's a whole group travelling together, and then the plot of the book then becomes about reuniting these various lovers with their lost loves.

This is mildly interesting. At least now we have a plot to latch onto, and it's nice to get some recognizable character arcs.

Although the resolution to these character arcs is a bit underwhelming--it turns out that the hero of this story is coincidence. All the key players just happen to run into each other at an inn, and shortly afterwards everything is sorted out. I've noted before on this blog that both Dumas and Dickens make overuse of coincidence as a plot contrivance, and now I can also add Cervantes to that list. But I actually didn't mind it so much. You almost expect it in an old book like this.

Then, later more strangers arrive at the inn, and one of them has a long backstory about how he was captured by the Moors and then escaped, and this backstory goes on for another 3 chapters.

I know, 25 pages doesn't sound like much, but remember (as mentioned above) these are big text-dense pages. And I'm a slow reader. At my pace, it was usually 2 or 3 days of reading to get through these side stories. And I found them really boring and couldn't understand what the point of them was. And this opinion was shared by the entire bookclub. We all made it through these sections, but it was a real slog. (Mind you, I'm sure that if we were to check the scholarly commentary, there would be all sorts of symbolism and hidden meanings in these stories that we were missing. But on the surface, they just struck us as boring, and it was frustrating to be pulled away from the main narrative for these long boring, seemingly pointless discursions.)

And then, finally, Part 1 comes to an end. Next is Part 2.

Part 2, as I noted above, was originally a separate book when it was first published. And it was published 10 years after the original. But the story in Part 2 takes place only one month after Part 1 has finished.

Within the world of Part 2, in that intervening month, the original Don Quixote was somehow written and published, and many of the characters read it. (As I also mentioned above, the conceit of Part 2 is that it exists in a world in which Part 1 is now published--an interesting bit of meta-fiction.)

Of course, it would have been impossible for the original Don Quixote to have been written, published, and so widely circulated in just one month, but this is another example of Cervantes playing with the reality of the narrative, and so it works as another meta-joke.

Don Quixote and Sancho themselves never read Don Quixote, but other characters have, and there are sections in which other characters talk to them about their exploits in the first book, and Don Quixote and Sancho ask questions about how they are portrayed.

In addition, Cervantes has more meta-fun by having the characters talk about some of the continuity errors in Part 1. And he also has his characters mention the criticism of the superfluous inserted stories in Part 1.

"One of the faults found with this history," said Carrasco, "is, that the author has thrust into it a novel, which he calls 'The Curious Impertinent'; not that it is ill writ, or the design of it to be disliked, but because it is not in its right place, and has no coherence with the story of Don Quixote." (p.386)

But there's even more meta-fiction humor going on in Part 2.

You see, in the years between when Part 1 was published and Part 2 was published, somebody else--someone who was not Cervantes--wrote an unauthorized sequel to Don Quixote. (*21) And this unauthorized sequel really ticked Cervantes off.

Part of the reason that the unauthorized sequel made Cervantes so mad is that it apparently included some gratuitous insults against Cervantes himself. Cervantes gives his rebuttal to these insults in his Author's preface to Part 2, and it's among the most entertaining parts of the whole book:

Bless me ! reader, gentle or simple, or whatever you be, how impatiently by this time must you expect this Preface, supposing it to be nothing but revengeful invectives against the author of the second Don Quixote. But I must beg your pardon; for I shall say no more of him than everybody says, that Tordesillas is the place where he was begotten, and Tarragona the place where he was born; and though it be universally said, that even a worm, when trod upon, will turn again, yet I am resolved for once to cross the proverb. You perhaps now would have me call him coxcomb, fool, and madman; but I am of another mind, and so let his folly be its own punishment. But there is something which I cannot so easily pass over; he is pleased to upbraid me with my age; as if it had been in my power to stop the career of time: indeed, had it been in the power of man to stop the career of time, I would not have suffered the old gentleman to have laid his fingers on me. (p.367)

So, in the world of Don Quixote Part 2, not only have the characters already read Don Quixote Part 1, but the unauthorized sequel is now floating around as well. So Don Quixote and Sancho also encounter characters who have read the unauthorized sequel, and ask them about events from it, and Don Quixote and Sancho have to correct the record and say that they never did those things, and they also criticize how simplistically they are portrayed in the unauthorized sequel. (*22)

With that he took the book from his friend, and gave it to Don Quixote. The knight took it, and, without saying a word, began to turn over the leaves; and then, returning it a while after: "In the little I have seen," said he, "I have found three things in this author that deserve reprehension. First, I find fault with some words in his preface. In the second place, his language is Arragonian, for sometimes he writes without articles. And the third thing I have observed, which betrays most his ignorance, is, he is out of the way in one of the principal parts of the history; for there he says, that the wife of my squire, Sancho Panza, is called Mary Gutierrez, which is not true, for her name is Teresa Panza; and he that errs in so considerable a passage, may well be suspected to have committed many gross errors through the whole history." "A pretty impudent fellow is this same history writer!" cried Sancho. "Sure he knows much what belongs to our concerns, to call my wife Teresa Panza, Mary Gutierrez! Pray, take the book again, if it like your worship, and see whether he says any thing of me, and whether he has not changed my name too." "Sure, by what you have said, honest man," said Don Jeronimo, "you should be Sancho Panza, squire to Signer Don Quixote?" "So I am," quoth Sancho, " and I am proud of the office." "Well," said the gentleman, " to tell you the truth, the last author does not treat you so civilly as you seem to deserve. He represents you as a glutton and a fool, without the least grain of wit or humour, and very different from the Sancho we have in the first part of your master's history." " Heaven forgive him," quoth Sancho; "he might have left me where I was, without offering to meddle with me..." (p.693-694)

Actually I take that back--it's not all the same kind of shenanigans as Part 1. Some of it is. But a lot of the people that Don Quixote runs into in Part 2 know who he is now (because they've read Part 1). So instead of being confused or angry about this delusional knight (which was the common reaction in Part 1), characters in Part 2 deliberately start messing with Don Quixote to see what his reaction will be, or they will deliberately contrive situations to goad Don Quixote on in order to get a laugh out of him.

This seems like it would be a lot of fun, and, to be fair, there are indeed several good jokes that are gotten out of this premise.

So then, throughout the whole rest of Part 2, Don Quixote is constantly upset at Sancho because Sancho is refusing to whip his own butt. And Sancho is constantly making excuses about how he is not quite in the mood to give himself the lashes just yet. Or Sancho is complaining that he doesn't understand why he has to whip his own butt in order for the enchantment to be broken when the enchantment has nothing to do with him.

It was genuinely funny. I chuckled to myself a lot reading those sections.

But (here comes the "but"), Part 2 also just goes on for way too long.

Don Quixote and Sancho end up stuck at the Duke and Duchess's castle for way too many chapters, and the jokes and pranks that the Duke and Duchess keep pulling on Don Quixote and Sancho stop being interesting after a while.

As I noted above, part of the reason that Part 1 was so funny was not because Don Quixote mistook one thing for another thing (that joke got old fast), but because of the surprised reaction of everyone around Don Quixote. But now with the Duke and Duchess actively controlling and stage managing all of Don Quixote's illusions, it's not quite as interesting. And it goes on for too long. (Did I mention yet that this book goes on for too long?)

In conclusion: Hopefully I don't come off as too negative about this book. As I mention in my review, there is a lot of very interesting stuff in this book. I had trouble forcing myself through the whole thing, but I definitely enjoyed a lot of aspects in it. And I haven't even talked about half the stuff in this book yet...

I Haven't Even Talked About Half the Stuff in This Book Yet

Oh, man, there's so much stuff I haven't even gotten to yet. The religious and historical aspects of this book (the constant talk about Christians, Moors and Jews which must have been a hot topic in Spain in 1600). A lot of the politically incorrect parts of the book (talk about the Ethiopians and their black skin, or derogatory comments about Muslims)....but this review is way too long already, and I've spent way too much time writing this review now. I've got a lot of other stuff on my plate, so I'm going to have to finish things here.

And really, there's no point in me feeling like I have to discuss every last thing in Don Quixote. As I mentioned above, the commentary on Don Quixote is already overwhelming. The last thing the world needs is another dissection of the themes of Don Quixote by an amateur reviewer. I'm hanging up my hat here.

I do, however, want to close by talking briefly about the subject I touched on in a blog post made back in January to remind me about how this book relates to Qanon and the January 6th insurrectionists, because it's something that's been on my mind a lot in the past couple months.

The Wordsworth Classics publisher's introduction by Stephen Boyd does a very good job of highlighting that one of the themes of Don Quixote is that it's not only Don Quixote himself who lives in a fantasy world. Almost everyone Don Quixote encounters are viewing their reality through the prism of overly romantic stories. The criminals and highway men that Don Quixote meets have been reading too many biographies of famous criminals, and have an overly romantic view of their own lives as outlaws. The shepherds and shepherdesses that Don Quixote meets have been reading too many pastoral romances, and have an overly romantic view of their life.

You can see, hopefully, how directly this relates to the insurrectionists of January 6th, who went out cosplaying as soldiers or dressed up as Vikings to try to live out their overly romantic fantasy about how they were saving the country from traitorous democrats.

But is it just these crazy rightwing nuts who are deluded, or are we all living in a fantasy world? Philosophy professor Justin E. Smith wrote of the event:

The problem with this is that (with a gentle shout-out to René Girard) in an important sense all culture is larping — our species is Homo larpens at least as much as it is Homo narrans or ludens. The Viking who put on a bear sark was larping too. I larp every day I get up and pretend to be a competent professor of philosophy who understands anything at all about how the world works. This is all of course well-trodden ground for twentieth-century philosophy. Jean-Paul Sartre’s analysis of the waiter who was trying too hard to be a waiter —dressing up as a waiter each day and studiously imitating the bodily motions he associated with waiterdom— put to rest, if only incidentally, Heidegger’s expectation that there might be some deeper way of conducting ourselves that we can deem “authentic”. It’s just fake waiters all the way down, and fake philosophy professors, and mirror neurons spreading cultural patterns from one individual to the next. Another word for all that fakeness is, precisely, “culture”. And this is the danger of talk of larping: it reasserts willy-nilly the opposing, and dangerous, notion of authenticity.

(It should hopefully make even more sense if you read it in context in the full article. Thanks to Whisky for the link.)

(*1) Regarding my friend who thought Don Quixote was the most beautiful thing he ever read: This is, needless to say, not my own evaluation. However these people are out there. I've encountered a couple more people like this on BookTube--people who claim Don Quixote is the most wonderful thing that they've ever read.

(*2) On The History of World Literature by John L. Voth: I linked to the whole series on Youtube back in 2017, but unfortunately the videos have been removed. (Not surprisingly, I suppose. The Great Courses series is, after all, copyrighted content that is sold for profit.) But if you can find a copy of it one way or another, it's recommended listening in my book.

This is, by the way, the second book now that I've picked up solely because I was fascinated by Professor Voth's description of it. The first book (or rather set of books) I read based on Voth's recommendation was The-Cairo-Trilogy by Naguib Mahfouz.

(*3) On the multiple narrators for Don Quixote: The whole idea is a lot of fun, isn't it? It strikes me as something straight out of Monty Python and the Holy Grail. (You may remember that movie was also constantly blurring the lines between the fictional story and the narration of the movie.)

It's a reminder that a lot of the meta-humor that we associate with 20th Century post-modernism is actually a lot older than we give credit for. Meta-humor is not unique to the modern age. (The other old book that springs to mind as using meta-humor to subvert the narrative is Tristram Shandy, but I'm not entirely sure I can count Tristram Shandy as a separate entry since, according to Wikipedia, it was directly influenced by Don Quixote.)

Although now that I've finished the book, I should add in the caveat that it turns out that the overlapping narrators wasn't as big a part of the book as Professor Voth had led me to believe. Yes, it is in the book, but it's only a handful of times that you actually get the overlapping commentary. Most of the time the narration is pretty straight forward.

(*4) On Part 2: Hopefully I'm describing this in a coherent way. But in case I've left anyone confused, I'll just borrow from Wikipedia's succinct description:

Part Two of Don Quixote explores the concept of a character understanding that he is written about, an idea much explored in the 20th century. As Part Two begins, it is assumed that the literate classes of Spain have all read the first part of the story. Cervantes' meta-fictional device was to make even the characters in the story familiar with the publication of Part One

(*5) More on Part 2: Although now that I've read the book, I should add another caveat here that (if memory serves) Professor Voth didn't make entirely clear. Don Quixote and his squire Sancho Panza themselves never actually read the original Don Quixote. Instead, they are told about its contents by the other characters. (Actually they receive reports not only of their depictions in the original Don Quixote but also of their depictions in the unauthorized sequel.)

(*6) On the idea of characters in a book being aware of the book itself: The idea of characters in a book being aware of the book itself is also something that the Flashman series makes use of--the conceit of the Flashman series being that it takes the characters from the public domain book Tom Brown's Schooldays and then follows their adventures in a world in which Tom Brown's Schooldays is in print. In the first book, Flashman admits that the readers will already be aware of him from Thomas Hughes depiction in Tom Brown's Schooldays. In Flashman and the Great Game, Flashman's character is confronted with the publication of Tom Brown's Schooldays, and many subsequent Flashman books have characters ask Flashman about the truth of Tom Brown's Schooldays.

In my video introduction to The Flashman series, I made the comparison with Don Quixote explicit. And I suspect author George MacDonald Fraser was consciously influenced by Don Quixote. (Although who knows--it could also just be a case of great minds thinking alike.)

Also, now that I think about, the Sherlock Holmes stories also have some elements of this. The conceit of most of the Sherlock Holmes stories is that Watson is writing the stories up for publication, and in some of the later Sherlock Holmes stories, Holmes will occasionally comment on Watson's previously published stories, which indicates that Sherlock Holmes himself has read some of the Sherlock Holmes stories.

...and what else? I'm sure there are other examples of this that I'm just not thinking of at the moment. Help me out in the comments, what am I missing?

(*7) On my habit of recommending very long and ambitious books to our book club: "Yikes -- do you give no thought for brevity?" Whisky Prajer chided me after reading my suggestions for book club. Yes, point well-taken. I probably was going a little bit overboard on the tomes.

(*8) On Tom's aversion to Don Quixote: ...and the thing was, Tom had previously indicated he'd be open to re-reading a few books he'd already read for the sake of some interesting discourse in our book club. But Don Quixote was emphatically not one of those books.

(*9) On giving up on Part 2: I don't know how common this is, but just anecdotally, there was at least one more guy in my office who had also tried Don Quixote but had given up on Part 2 as well. Before I started reading the book, this struck me as strange. I mean, for one thing, by the time you get to Part 2 you're halfway through the book already. You might as well just suck it up and finish at that point, right? But plus, based on Professor Voths' description, Part 2 sounded like the most interesting part. "Why would you stop there?" I thought.

Little did I know how close I would come to also giving up on Part 2 myself. If I wasn't in the habit of publicly declaring which books I start and which books I finish on this blog (and thus creating some accountability for myself), I probably would have also just quietly stopped reading somewhere in the middle of Part 2.

(*10) Tom moved to Columbia: On the slim chance that anyone new around here stumbles upon this blog--I am living and teaching English in Saigon. So the bookclub was made up of transient expats.

(*11) Wordsworth Classics: These being the editions of classic books most readily available in Saigon, almost all of the other classic books I've read during my stay in Saigon have been Wordsworth Classics editions. (For example: Tom Sawyer, Huckleberry Finn, The Count of Monte Cristo, Brothers Karamazov, Frankenstein). So at this point I'm well aware with the faults of the series.

For one thing, for anything in translation, they always go with an old translation that's already in the public domain. In this case, they've used a 1700 translation of Don Quixote by Peter Motteux.

The good news is that despite being 400 years old, it's actually pretty readable. However, it is also on a bit dry. I wonder if a newer modern translation would have pulled me into this book a bit more? (And perhaps caused me to get through this book a bit quicker?)

The other problem that I've noticed consistently with Wordsworth Classics is that their endnotes are so inconsistent and random. (The translator's comments appear at the bottom of the page as footnotes. The publisher's explanations appear at the back of the book as endnotes.) For each book, Wordsworth Classics hire a literature professor to write a brief introduction, and add explanatory endnotes throughout the book. But the endnotes just pop up randomly. There could be several numbers on one page, and then we could go 100 pages without any endnotes. Several allusions that are obvious to most literature people are endnoted (such as basic Biblical allusions), but then for most of the obscure allusions the reader is left with no help at all. Sometimes the endnotes are useful, but they're so inconsistent as to always leave you wondering "But why an endnote suddenly here, and nothing for the previous 10 allusions I missed?"

My best guess is that the poor literature professor isn't being paid a lot, and he just goes through and randomly endnotes whatever allusions he knows off the top of his head, because it's been this way for all of the Wordsworth Classics books I've read. (In this particular case, the culprit is one Stephen Boyd of the University of College Cork, but I don't think he's to blame since it's been this way with all the other Wordsworth Classics). But it's a particular pity with Don Quixote because there are so many allusions to other books of knight errantry which would have been nice to know more about. But then, I suppose for a book as long as this one with as many allusions as this one, fully endnoting it would be an impossible task.

On a positive note, though, the 12 page Introduction that Stephen Boyd provided at the front of the book was very useful.

(*12) The comic book illustration: I usually like doing something visually appealing and a bit pulpy for these started posts, and after doing a Google Image search, I had a hard time finding an actual book cover that looked like any fun. So I went with the comic book version.

And also I shouldn't say we all finished Part 1. One book club member gave up. But I won't shame her here.

(*14) On Part 1 being foggy in my mind: I've been doing my best, though, to keep it fresh in my mind. I've been listening to the free librivox audiobook of Part 1, and I've also been re-reading parts of Part 1 while I've been writing this review.

(*15) On my progress with Don Quixote being hampered by getting distracted by other books: Actually the real thing that hampered my progress on Don Quixote was the same thing that always hampers my reading--my Internet addiction, and all the time I waste on Youtube, Twitter, Facebook, et cetera. But this is such a perennial problem for me (I've-been- lamenting - this - every - year), that it seems almost uninteresting for me to mention it again here. Certainly if I was able to get my Internet surfing under control and read more books instead, then I'd have a lot more books to report on every year. But to the extent that I've already resigned myself to the fact that I only manage to get a limited amount of books read each year, then the fact that I kept getting distracted by other books is the reason it took me so long to finish Don Quixote.

(*16) I was involved in 2 other book clubs at the time: 1 book club for general fiction (this is, of course, the exact same book club I've already mentioned--the very same bookclub that we attempted to read Don Quixote in), and 1 book club for professional development.

Actually there were 3 book clubs if you count our other co-workers attempt to get a 3rd book club going for general non-fiction, but I'll deal with that book club on another day.

All of these book clubs fizzled out in the fall of 2018, but at least for the first several months I was trying to finish Don Quixote, they did a lot to distract my attention.

(*17) On Getting Distracted by Other Books: To be precise, since starting Don Quixote on December 17, 2017, I have finished, and reviewed on this blog, 34 other books.

2. The Civil Wars by Appian of Alexandria March 5, 2018

4. The Language Teaching Matrix by Jack C. Richards--Revisited, March 28, 2018

5. A Framework for Task-Based Learning by Jane Willis , May 27, 2018

6. Speaking by Martin Bygate, July 2, 2018

7. The Martian Chronicles by Ray Bradbury , July 11, 2018

8. Palace of Desire by Naguib Mahfouz , July 20, 2018

9. The Land of Stories: The Wishing Spell by Chris Colfer, September 5, 2018

10. Sugar Street by Naguib Mahfouz, September 18, 2018

11. Americanah by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, October 8, 2018

12. Teaching Unplugged by Luke Meddings and Scott Thornbury, October 9, 2018

13. An A-Z of ELT by Scott Thornbury (First Edition), October 18, 2018

15. The Wilful Princess and the Piebald Prince by Robin Hobb, December 1, 2018

16. The Enchanted Castle by Edith Nesbit, December 18, 2018

17. Coming Up for Air by George Orwell December 20, 2018

18. Claudius the God by Robert Graves , January 2, 2019

19. The Handmaid's Tale by Margaret Atwood, January 14, 2019

20. Teaching Young Language Learners by Annamaria Pinter, February 6, 2019

21. Bound for Glory by Woody Guthrie, February 7, 2019

22. Sweden by Matthew Turner, September 28, 2019

23. Syllabus Design by David Nunan, November 5, 2019

24. The Golden Fleece by Robert Graves, January 28, 2020

25. Designing Language Courses: A Guide for Teachers by Kathleen Graves , April 2, 2020

26. Nine Princes in Amber by Roger Zelazny , April 11, 2020

27. Learning One-to-One by Ingrid Wisniewska, June 3, 2020

28. Being Wagner: The Triumph of the Will by Simon Callow June 26, 2020

29. The Guns of Avalon (The Chronicles of Amber #2) by Roger Zelazny, July 19, 2020

30. Age of Myth by Michael J. Sullivan August 17, 2020

32. Tales of Troy and Greece by Andrew Lang November 8, 2020

33. Frozen (Heart of Dread #1) by Melissa de la Cruz and Michael Johnston December 1, 2020

34. Mrs. Frisby and the Rats of NIMH by Robert C. O'Brien December 12, 2020

Plus finished, but not yet reviewed, Chomsky's Universal Grammar: An Introduction. And that's not even getting into all the books I started but abandoned during this period.

Cervantes was Shakespeare's contemporary, so I imagine that reading him in the original Spanish would be similar to reading Shakespearean English.

The translation I have (as I mentioned in footnote 11) is from the year 1700 translation, but it still presented no difficulties. The prose style was a bit stiff and formal (as older books are), but I had no trouble understanding anything. I suspect a more modern translation would be even easier yet.

I'm also told that much of the humor in the original comes from the various styles of speech which were used, and apparently this doesn't translate at all.

And I'm sure that the original audience back in 1605 understood all the references and satire that are nowadays lost on modern readers.

...but, in spite of all that, there is still a lot of humor in this book that is timeless, and translates perfectly well to a 21st Century English reader.

(*20) On all the medieval legends and stories referenced in Don Quixote: There's tons of stories and names constantly being referenced in Don Quixote. This is where good footnotes would really come in handy. Sadly (as I mentioned in footnote 11), the Wordsworth Classics edition is lacking in this regard. But, nowadays we have Wikipedia, so if you're so inclined, you can stop reading to look up any references that make you curious.

Among several interesting little tidbits I picked up from Don Quixote was the legend of Roderic. Don Quixote only made passing reference to it, but by looking it up on Wikipedia, I was able to get the full story.

Roderic was the last Visigoth King of Spain (before the Muslim invasion). There's a whole little legend about how Roderic's downfall, and the Muslim invasion of Spain, happened because Roderic raped the daughter of one of the nobles. (Similar to the Roman legend of the rape of Lucretia.) For centuries, this legend was treated as historical fact. Read all about it on Wikipedia HERE.

If you find those little bits of history and legend interesting, there are a lot of those allusions in Don Quixote. So it's another bonus of reading the book.

However, there are enough references to the events of the unauthorized sequel that I almost felt like I was missing something for not having read it. I feel like in order to do a thorough study of Don Quixote, you would need to read the unauthorized sequel as well to get all the references.

(I have no intention of doing this, but someone who wanted to do a thorough study of the book would no doubt need to do this.)

I did a brief Google Search and was somewhat surprised to find that the unauthorized sequel doesn't appear to be more widely available on the Internet. I was sure it would be on project Gutenberg or something, but no luck. There are scanned copies of an old edition on archive.org, but nothing in a convenient text form.

Of course, if you really wanted to do a thorough study of Don Quixote, you'd also have to read Amadis of Gaul, and probably about a half dozen other chivalric romances in order to get all the references. So admittedly it's difficult to know where to start with the background reading for a book like this.

Weekly Reading Vlogs:

March 28, 2021 p.226-276 ,

Video Review (Playlist HERE)

No comments:

Post a Comment