Started: November 09, 2022

Finished: December 28, 2022

(This review is written using my new format for book reviews.)

Background Information

Background Information on The Peloponnesian War Generally

The Peloponnesian War is the name for a long period of conflict between Athens and Sparta from 460 to 404 B.C. It's similar to the Napoleonic Wars in that it's actually a series of conflicts--there were periods of peace intermixed with renewed war. But, like the Napoleonic Wars, historians also view it as one continuous conflict.

The Peloponnesian War is (potentially) interesting for a number of reasons (I'll get around to discussing those down below), but it's chiefly historically important because:

1) It occurred right smack during the golden age of ancient Greek civilization, and it so influenced a lot of the literature and philosophy produced during that time. (Literature and philosophy that would later go on to become the foundation of Western Civilization.)

2) It exhausted Athens and Sparta, and consequently marked the end of the Greek City state era, and thus paved the way for the armies of Alexander the Great to march in and conquer Greece.

The Peloponnesian War is infamous for confusing and frustrating students. (I don't think the Peloponnesian War is currently being taught anywhere in secondary schools anymore, but it still has a notorious reputation in the cultural memory--a lingering cultural hangover from the days when classical education was still part of the school curriculum.) It's a long and confusing conflict that involved the whole Greek world, and also had different cities switching sides back and forth during different stages of the war.

It also was a conflict that went all over the map--the conflict went all up and down the Greek Peninsula and all over Aegean Sea. The war even reached as far as Italy and Sicily. All the Greek city states were involved, plus other nations (like Persia, Egypt, Macedonia and Carthage) got sucked in at one point or another.

For this reason, people often refer to the Peloponnesian War as the World War of the ancient world.

Our information on The Peloponnesian War comes from a number of different sources, but it's chiefly associated with the classic History of the Peloponnesian War by Thucydides (W). But that's not the book I'm reviewing today. I'm reviewing Donald Kagan's synopsis of Thucydides: The Peloponnesian War by Donald Kagan

Background Information on this Specific Book: The Peloponnesian War by Donald Kagan

Donald Kagan is a professor at Yale University, and considered an expert on the Peloponnesian War. He had previously written a 4 volume history of the Peloponnesian War for scholarly audiences, but was convinced by one of his colleagues that there was a market for a one volume history of the war for general readers. The book was very successful. As Donald Kagan says HERE:

I wrote a one-volume history of the Peloponnesian War and it sold 50,000 copies of the damn thing. I was truly amazed; so was my publisher. But I think I shouldn't have been amazed, because for maybe a century now people have been studying Thucydides and the war, or when they have not been studying, they've been hearing about it; references have been made to it by distinguished people. General Marshall referred to it in a famous quotation when he was Secretary of State and people keep talking about it, and so the curiosity I think rather than the familiarity--curiosity about what is this all about--may account for this...

I mentioned above that this was a "synopsis of Thucydides", but Donald Kagan actually draws on several other ancient historians (Plutarch, Xenophon, etc) to complete his picture of the Peloponnesian War. At the same time, however, it's obvious to even an uniformed reader like myself that Donald Kagan is only giving a brief summary of a much more complex history.

Why I Read This Book (a.k.a. how I became interested in the Peloponnesian War)

I've repeated this story a few - times - now, but back when I was in middle school, I was interested in Greek and Roman history. By high school, I had gravitated to an interest exclusively in Roman history (for all the reasons I mentioned HERE), and so consequently never really read up on Greek history or the Peloponnesian War.

I started college as a classics major, but by sophomore year I decided that I was more interested in modern history--I was fascinated by the drama of the revolutionary period of the 19th Century, and the ideology of the enlightenment. So I switched majors to a general history degree.

But ever since then, I've been getting hints that I may have been too quick to disregard the ancient world--some of the ideology that so attracted me to the 19th century actually had analogues in the ancient world.

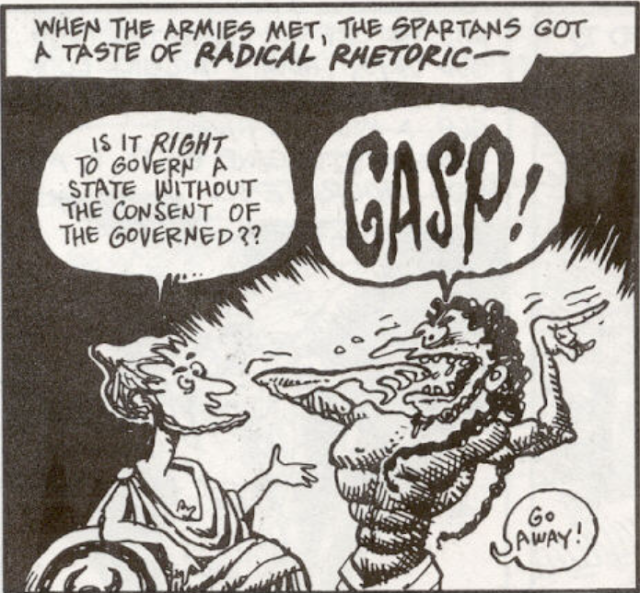

In particular, in 2006 I was at the public library, and I was flipping through The Cartoon History of the Universe (W), and I came across these panels discussing the conflict between Athens and Sparta as a conflict of ideology.

|

| Taken from: https://2.bp.blogspot.com/hoy83tAHGK9USjMqNj5VIuJDfl9b3xOXS47wf0iu2_MIdXh4xuSr7g-g8iclCkDa39-1d3G2AR7HrmHPP0ooyMoamKg44PVAk3SyNlN5YDXM6QTdLDxwCZisqFEarPJq21MHcA=s1600 |

So, obviously the "joke" here is that the comic is using the language of the enlightenment to describe the ideology of the ancient world:

...but it got me thinking. These type of conversations must have taken place in ancient Greece, right?

I had, of course, known that Athens was a democracy. Every schoolboy learns that. But my secondary education had given me the impression that Athens just happened to be a democracy in the same way that Persia just happened to be an empire. There was no discussion about how Athens became a democracy, or what the ideological struggles in ancient Greece were. But obviously in the ancient world, democracy was not the norm. So it must have been considered a radical idea. There must have been heated debates, discussions and arguments about democracy in ancient Greece just as there were in the 19th century.

Before this, I had the view of the Peloponnesian War that I think a lot of people had--a long series of pointless battles between two neighboring cities. After this, I had the idea that there might be an interesting ideological component to the Peloponnesian War.

2006 was nearly 20 years ago now. So admittedly it's taken me a long time to finally work my way around to actually reading about the Peloponnesian War.

Well, what can I say? Now that I'm middle aged, there are actually a lot of things I've been meaning to read about for the past 20 or 30 years that I'm only getting around to now. (You may have noticed I've been making this - same - apology a lot recently.) I wish I was a better reader, but that's about all I can say.

Although in 2008, I did pick up A People's History of the World by Chris Harman from a bookstore in Japan, in no small part because I was hoping that Chris Harman would connect the ideological struggles of the ancient world to the modern revolutions. And I was subsequently disappointed when he completely dropped the ball on this. As I wrote in my review at the time:

The pity is, the historical record is a lot richer than Harman’s book acknowledges. We know a surprising amount about the class struggles in the ancient world. Although ancient historical sources can sometimes mix truth with legend, they have left us with a wealth of material. We know, for example, a lot about the ideological battles between the warring Greek city states.

("We" in that quote refers to the shared cultural knowledge of the collective "we". I personally only had a vague idea about this history.)

The interest in the ideology of the Greek world popped up again when I read the Alexander the Great trilogy by Valerio Massimo Manfredi, and I was intrigued again by how Alexander (at least in Manfredi's description) viewed himself as restoring democracy to the Greek city states under Persian domination. It was yet another connection of democratic ideology with Greek history and culture.

And, in my review of Fire from Heaven by Mary Renault, I wrote about how Mary Renault wove in details about the aftermath of the Peloponnesian War into her story about the rise of Alexander the Great. And this further intrigued me.

As for Donald Kagan's book, I first heard of it when I read a review by Blogging the Canon (a blogger I discovered when doing my review of Kim, and who I've continued reading ever since). Blogging the Canon did a post on his experience reading Thucydides, and in that post he mentions how useful he found Donald Kagan's book as a supplement to Thucydides. To quote from his review:

As I was reading Thucydides, I also read Donald Kagan's book "The Peloponnesian War" at the same time. Kagan is a scholar of Greek history and of Thucydides, and his account both summarizes Thucydides and, perhaps more importantly for me, gives an analysis of Thucydides; specifically an analysis of the events he describes, and what other ancient writers wrote about the war. Kagan's book greatly enriched my understanding of just what the hell Thucydides was talking about at certain points, and made a great companion to Thucydides book. Plus he tells what happens after Thucydides' history breaks off.

It was based on this recommendation that in 2016 I listened to the Open Yale Courses Ancient Greek History with Donald Kagan and reviewed it on this blog. As I wrote in my review, I found it fascinating stuff.

When I was back home in the US for Christmas during 2019, I finally picked up a copy of Donald Kagan's book. (It was still popular enough that it was readily available on the bookshelves at my local bookstore. I didn't have to special order a copy or anything.)

And I've been waiting to get around to it ever since then. (I wanted to finish Herodotus first, since Herodotus's histories come first chronologically. But after finishing Herodotus, it was finally time to get into the Peloponnesian War.)

Of course, Blogging the Canon read Donald Kagan's book alongside of Thucydides, as a companion and supplement to Thucydides. And I think this is a fairly common usage of Donald Kagan's book. My fellow booktuber Revenant Reads also discussed reading the two as a set in his video from October 2021 here. Although, I left a brief comment:

I've got Donald Kagan's book on my shelf next. I'm planning on reading Donald Kagan's book before I attempt Thucydides, based on Steve Donoghue's philosophy of starting with the more accessible reading and then working your way up to the difficult stuff.

You see, the great Steve Donoghue, in one of his youtube videos, once made a point that when you're starting on a new area of interest, you don't get any points for plunging into the most difficult material first. Instead, start with the easiest, most accessible material, and gradually work your way up to the difficult stuff.

Thucydides has a reputation for being a bit difficult and confusing, so I figured I would start with Donald Kagan's popular history first, and then (possibly) move on to Thucydides after I had finished Kagan's book.

I should also note that while reading Donald Kagan, I supplemented my reading by going back and re-listening to some of the relevant lectures from his Yale Open Courses lectures.

To further supplement, I started listening to the relevant episodes from The History of Ancient Greece Podcast by Ryan Stitt (available on Google podcasts HERE).

I also found both of these sources useful in filling in my knowledge on the 50 year period between the end of the Herodotus and the beginning of the Persian War (W).

[Um... Since I brought up Ryan Stitt, I feel like I have to mention that 2 years ago Ryan Stitt got called out for allegedly harassing women in the classics department. See a blogpost about that HERE. I really don't want to get sidetracked by talking about that controversy though. This book review is way too long already as it is. All I'll say for now is that I don't believe the sexual harassment allegations affect the informational content of his podcasts--so I thought his podcasts would still contain useful information for me whether or not he's a sex creep. But you'll have to make up your own mind about how you feel about listening to his podcasts.]

Other Reasons That the Peloponnesian War Might Be Interesting

It strikes me that in the above narrative, I left out several other reasons why the Peloponnesian War might (potentially) be interesting. So let me add a few of those here.

I should, of course, acknowledge that part of the reason I'm writing all this is that I fully know there are a lot of reasons why the Peloponnesian War is not interesting--it's a long confusing war that just goes on and on and on. So I should perhaps give a few more reasons why I thought it was worth my time to read about (and why it potentially might be worth your time as well.)

For starters, the Peloponnesian War occurred right during the middle of ancient Greek's golden age--when ancient Greece was right in the middle of turning out all the literature and philosophy that would go on to define the Western World.

It's a funny thing when you think of "golden ages" in history. After all, history is thousands and thousands of years long, and covers all the human civilizations on the globe. And yet, human creativity and ingenuity does not seem to have been equally distributed across this domain of time and space--the literature and ideas that we still remember and talk about today come from just a few golden ages--small pockets of geographical areas in a very compressed time frame: The Italian Renaissance, The Augustan Age, etc. And, of course, Ancient Athens.

The Golden Age of ancient Athens was only about 100 years, and that 100 years included the Peloponnesian Wars. (Or it was ended by the Peloponnesian Wars, depending on who you ask. But either way it was right around the Peloponnesian Wars.) Therefore, so much of the philosophy and literature of golden age Greece was shaped by the Peloponnesian Wars.

For example, Socrates himself actually took part in the Peloponnesian Wars--he fought in some of the key battles, and played a key political part in one of the major political controversies of the war (W). Other prominent politicians during this time were friends or students of Socrates. And some of them show up in Plato's dialogues (see, for example, here). (And speaking of Plato, his formative years were also shaped by the Peloponnesian Wars.)

Also a lot of surviving Greek plays are commentaries on the Peloponnesian Wars.

For example, Lysistrata (W)--a famous antiwar play in which the women of Athens refuse to have sex with their husbands until their husbands agree to end the war.

(I actually saw Lysistrata when I was in high school. Calvin College theater company was putting on a production of it, and my mother thought I'd be interested since I was interested in ancient Greece. However, I had no idea at the time that it was about the Peloponnesian Wars specifically. I just thought it was some sort of generic antiwar play. It was only after I started learning about the Peloponnesian Wars that I started appreciating the historical context of that play.)

Or The Trojan Women by Eurpides (W), which is supposedly a commentary on the brutality of the Peloponnesian War.

Or the play Oedipus Rex by Sophocles (W), which, according to Ryan Stitt, is possibly a commentary on Greek politician Pericles during the Peloponnesian War. (The playwrights Eurpides and Sophocles also both fought in the Peloponnesian War themselves.)

Etc, etc, etc. There were tons of Greek plays and philosophical treatises written during the Peloponnesian War period.

Despite my slow reading progress over the years, I still have this wild dream of someday going back to the classics and reading the foundations of Western Civilization. (This was, as I mentioned, the impetus for my read-the-Bible project). And it occurs to me that if I ever tried to follow through on this, I would want to understand the Peloponnesian War so that I could understand all the Greek literature and philosophy written around it.

Plus, as some of the works listed above illustrate, a lot of the plays produced during the Peloponnesian War period was antiwar. So this would tie in nicely with my interest in - antiwar - literature - through - the - ages.

And then there is the fact that the Peloponnesian War coincided with the period of most radical democracy in Athens. So studying the politics of Athens during the Peloponnesian War is studying how a direct democracy functions during war.

I've mentioned before how anarchists sometimes look to the direct democracy of ancient Greece as a model for true democracy, and so this period ties in with my interest in anarchism as well.

However, this period also presents a problem for small "d" democrats or anarchists. That is, democratic Athens behaved as an imperial power during this time, and also committed a number of wartime atrocities.

And this is a point Noam Chomsky has made before. It is often pointed out to Chomsky that he is very critical of US foreign policy, despite the fact that the US is one of the freest countries in the world. Chomsky points out that Athens was the freest city in the ancient world, but Athens still behaved as an imperial power. In the movie Manufacturing Consent, Chomsky says here:

..it ends up being a very free society which does a lot of rotten things in the world. Okay? There's no contradiction there. I mean, you know, Greece was a free society by the standards of Athens, you know, it's also a vicious society from the point of view of its imperial behavior. There's virtually no correlation, maybe none, between the internal freedom of a society and its external behavior.

So the Peloponnesian War is worth studying to examine the problems of democracy and empire.

And finally, in the 20th century, the Peloponnesian War was studied as an analogue to the Cold War. Donald Kagan mentions in the clip I linked to above that it's been studied for years in military academies. And Whisky Prajer also chimed in in the comments a few weeks ago to let me know that Thucydides history of the Peloponnesian Wars was required reading for his college course on the Cold War:

In the mid 80s if you wanted to take A History Of The Cold War in university you were expected to read A History of the Peloponnesian War by Thucydides. So I'm just glad when someone else reads it.

The reasons so many people saw an analogy to the Cold War are (I think): Athens and Sparta were both the superpowers of the ancient world, just like the USA and the USSR were to the 20th Century. Because they were both equally strong, a war between them would be devastating for both of them. And yet, they both sought to dominate the Greek world, so sooner or later they were bound to come into conflict. Because a war would be so disastrous, the objective of diplomacy on both sides was to press as hard as they could to secure a peace that would be most advantageous for themselves, but without actually pressing too hard so that they fell into a war. (In his book, Donald Kagan reveals step-by-step all the diplomatic maneuverings that both sides used to try to preserve their geopolitical interests without actually falling into war--until they eventually did fall into the war.)

Both Athens and Sparta relied on a huge network of allies for their mutual security. There appears to have been an ideaological component to these alliances (most of Sparta's allies were oligarchic societies, many of Athens allies were democracies.) But the ideological component was not the sole consideration--Athens occasionally made war on fellow democracies if it suited their larger strategic aims. All of this is, of course, analogous to NATO and the Warsaw Pact.

But, as Donald Kagan also points out in his book, controlling these allies became a problem for both sides. There were numerous times when either Sparta's or Athen's hand was forced because of overly aggressive allies that they could not fully control. (Although war never broke out between the US and the USSR, I believe there are numerous analogues in the Cold War for mini-crises that resulted because of allies who tried to act independently--HERE, for example.)

So, those are all the reasons why I think this subject could be potentially interesting.

Now, Donald Kagan himself doesn't touch on all these subjects. (He's definitely more interested in some themes than in others.) But I think his book provides useful background for anyone who would want to go further into any of these subjects on their own. And on that basis, I'd recommend it to anyone interested in the subject.

But before I get any further into the review, maybe this would be a good point to highlight which of these themes Donald Kagan actually is interested in:

What Themes Donald Kagan is Interested In

I should make clear that Donald Kagan has written a history book here, not a philosophy book. Much of the book is just a chronicle of which battles happened in which order. He's got a lot of history to get through in just 500 pages, so he doesn't often pause to moralize on the lessons.

But he does get a bit more philosophical in his Open Yale Course Lectures, and so it's a bit easier to pull out themes from there. (If you're going to read this book, I really recommend you listen to Donald Kagan's lectures as a supplement. They complement each other really nicely.)

In those lectures, Donald Kagan seems very interested in the lessons of The Peloponnesian War for the study of modern international relationships. The dilemmas of war and peace faced in modern politics Donald Kagan believes has analogues in the Peloponnesian War.

I should note that Donald Kagan is not a pacifist. He believes that war sometimes is necessary, and that if war is going to be inevitable, it's sometimes better to start the war when you're in a strong position rather than delay the war until you're in a weaker position. But the central dilemma is trying to predict when the war is inevitable, and that's what he finds so interesting about the Peloponnesian War.

Also, in the book, there are various times when Athens has the opportunity to negotiate a peace. During these times, Donald Kagan explains that there is a pro-war faction in Athens, and a pro-peace faction. From Donald Kagan's book, I definitely got the impression that he was not sympathetic to the pro-peace faction. Donald Kagan believes that once you get into a war, it's important that you don't negotiate a peace that will just restore the status quo, because that means that you will just return to the original conditions--the conditions that were responsible for bringing about the war in the first place. Once you're in the war, you want to try to hold out for a victory that will establish you in a stronger position than the original status quo. For this reason, Donald Kagan seems critical of the peace faction in Athens for wanting to negotiate peace too early on the basis of restoring the status quo. Donald Kagan believes that they were giving into war-weariness, which he seems to view as a weakness of character, rather than having a valid ideological viewpoint.

[Although in his lecture series, he at one point implies that Athenian hubris probably caused Athens to miss some good opportunities to negotiate a settled peace. So, like I said, the lectures and the book complement each other nicely.]

Consequently, Donald Kagan's not really interested in talking about the various antiwar plays that were being produced in Athens during this period. (He mentions briefly one antiwar play, Peace by Aristophanes (W), but only to criticize the contents of it.) So if you're looking for a history that seriously examines the antiwar movement in Athens, you're going to have to look elsewhere.

As for my personal views, I have for years now considered myself a pacifist. But now that I'm middle-age, I'm trying to be less ideologically rigid about any of my accepted positions--that is, I try to always consider the possibility that I might be wrong about the things I believe. So I tried to read Donald Kagan's book with an open mind.

Donald Kagan is also much more politically conservative than I am--this is something that was evident from listening to his lectures (as I noted in my review at the time), as well as something that is clearly stated on his Wikipedia bio.

But this doesn't mean that Donald Kagan is so conservative as to be anti-democratic. On the contrary, Donald Kagan is a defender of the idea of democracy, and here I am much more in sympathy with him.

As Donald Kagan notes in his book, for many Greeks the failure of Athens during the Peloponnesian War was taken as a failure of democracy. And the historian Thucydides apparently blamed a lot of the poor decisions that Athens made during the war on the problem of democracy--the tendency of the gullible masses to be easily mislead by unscrupulous politicians.

Donald Kagan, however, tries to rehabilitate democracy in his retelling of the Peloponnesian War. He points out that a lot of the decisions that the voters in Athens made weren't actually as stupid as Thucydides thinks they were. He explains that there may actually have been some sound logic behind these decisions. And in cases were democratic Athens actually does do terrible or stupid things, Donald Kagan points out that although these actions were horrific, they did not occur because of democracy. Rather, these are the types of wartime atrocities or blunders that have occurred throughout history regardless of the type of government.

The Reading Experience

While I was carrying this book around with me, people would occasionally ask me how it was. "It's both really fascinating and really boring at the same time," I would say. "If that makes any sense."

I'll deal with the boring stuff first.

At its worst, this book can read like a long list of battles in a war that just goes on and on and on.

I found this side of things very tedious. And this is, unfortunately, a major part of the reading experience of the book.

Because there are so many military engagements to get through in 30 years of war, Donald Kagan doesn't get bogged down in the details of anyone battle. And occasionally the book can seem like just a list of which towns the battles were fought at instead of any descriptions. But occasionally he gets a little bit into the troop deployments, and the various military tactics that caused these battles to be won or lost.

I found it all very boring.

I should note here that this is just a personal preference.

When I was a history major back in college, a number of my classmates were obsessed with military history. You know, the kind of guys who love talking about maps, and troop movements, and flanking maneuvers, and cavalry deployment, etc. Those kind of guys would love this book. (And if you're one of those guys, be sure to check this book out.)

Me, personally, I'm more interested in the ideological battles than in the military history.

Although, as I was reading this book, I told myself that I really shouldn't dismiss the military aspect of history. Quite often, ideological realities are dictated by military outcomes. As I wrote in my review of The Civil Wars by Appian of Alexandria:

One also gets the impression from Appian that military might, not ideas, ultimately causes the change in history. The reason Rome transitioned from a republic to an empire is not because Antony and Octavian had the better ideas for government, but just because they had the superior military tactical skills.

Donald Kagan makes a very similar point in his book:

The defeat of Athens in the war was also a blow to the prospects for democracy in other Greek cities. The influence of political systems on people outside them is closely connected with their success in war. The democratic constitution of a powerful and successful Athens was a magnet and a model for others, even in the heart of the Peloponnesus. Athens' loss in the war against Sparta was taken as proof of the inadequacy of its political system; Athenian failures were seized upon as democratic errors; ordinary human mistakes and misfortunes were judged to be the peculiar consequences of democracy. (p.488-489)

So, I don't get to skip the military stuff just because I find it boring (I told myself). This is stuff I need to pay attention to.

But... I'm not sure how much of it I really absorbed into my long term memory. I mean, I dutifully slogged through all the battles when I was reading this book, and I told myself that I was educating myself. But am I going to be able to remember all these military battles 5 years from now? I'm already starting to forget all about the various battles. (When I got to the end of this book, I realized that I could only vaguely remember the battles that occurred at the beginning.)

The thing that really fascinated me about this book was all the dramatic personalities. There was the conservative Athenian statesman Cimon, and the demagogue Pericles (who was paradoxically both a radical democrat, and a sort of populist autocrat), and the flamboyant, but completely amoral, Alcibiades, etc. All of these figures fascinated me, and here I really wished the book were longer, because I wanted to hear more about them. But Donald Kagan has so much material to get through that these personalities are only mentioned very briefly.

Also, this book isn't all military. There is some interesting political stuff that comes into this book. Just when I was beginning to get sick of all the war stuff, there's an oligarchic coup that happens in Athens. And Donald Kagan takes a bit of a detour to talk about the ideological conflict in ancient Athens between oligarchs and democrats. And then as the coup plays out, the story then shifts to a kind of civil war within Athens, in which the democrats struggled to overthrow the oligarchic regime, and how this whole thing affected the moral of the soldiers, etc. I found that whole section of the story to be utterly fascinating.

So, yeah, there is definitely some interesting stuff in this book if you're willing to slog through the uninteresting stuff to get to it.

On the whole, I'm glad I read it.

Extended Quotation

[For this extended quotation, I decided to be nice and quote from one of the more interesting sections of the book. I could easily have quoted from a less-interesting section--talking about siege wars or cavalry deployments--but what fun is that? Better to show what the book has to offer when it's getting into the good stuff. So this is from the section on the oligarchic coup. It's Donald Kagan setting up the anti-democratic ideology that had always existed in the background among the aristocratic elite in democratic Athens.]

Some aristocrats, however, never abandoned their contempt for popular rule--a prejudice that had strong roots in Greek tradition. In the Homeric epics it was the nobles who made decisions and gave orders, while the commoners knew their place and obeyed them. In the sixth century the poet Theognis of Megara wrote bitterly as an aristocrat whose world was overthrown by political and social changes, and his ideas had a powerful influence on enemies of democracy well into the fourth century. Theognis divided mankind into two types based on birth: the good and noble, the bad and base. Because the noble alone possesses judgment (gnome) and reverence (aidos), he alone is capable of moderation, restraint and justice. The mass of the people lack these virtues and are, therefore, shameless and arrogant. The good qualities, moreover, cannot be taught; “It is easier to beget and rear a man than to put good sense into him. No one has ever discovered a way to make a fool wise or a bad man good. … If thought could be made and put into a man, the son of a good man would never become bad since he would obey good counsel. But you will never make the bad man good by teaching” (Theognis 429-438).

The views of the Theban poet Pindar, who lived past the middle of the fifth century, were also highly esteemed by the Athenian upper classes. His message mirrored that of Theognis: the nobly bon were inherently superior to the mass of people intellectually and morally, and the difference could not be erased by education.

The splendor running in the blood has much weight.A man can learn and yet see darkly, blow one way,then another, walking everon uncertain feet, his mind unfinished andfed with scraps of a thousand virtues.(Nemea 3.40-42).

Only the natively wise can understand:

There are many sharp shaftsin the quiverunder the crook of my arm.They speak to the understanding; most men need interpreters.The wise man knows many things in his blood; the vulgar are taught.They will say anything. They clatter vainly like crows against the sacred bird of Zeus.(Olympia 2.83-88)

To minds shaped by such ideas, democracy was foolish, at best, and could become unfair and immoral, as well. The Constitution of the Athenians--a pamphlet written in the 420s by an unknown author often called “The Old Oligarch”--reveals the discontent that some in Athens felt during the war: “As for the constitution of the Athenians, I do not praise them for having chosen it, because in choosing it they have given the better of it to the vulgar people (poneroi) rather than to the good (chrestoi)” (1.1) They use lots for positions that are safe and pay a salary but leave the dangerous jobs of generals and commanders of the cavalry to election and the “best qualified men” (Constitution of the Athenians 1.3)

***END QUOTE. p.362-363. The ellipsis in the Theognis quote is from the original.***

Other Notes

* I've complained in the past a - lot - about - endnotes in books, but fortunately Donald Kagan doesn't use them. There are a couple footnotes (at the bottom of the page), but no flipping to the back of the book to find the endnote. So that's another point for this book. And the maps are integrated into the main text (rather than being buried at the back of the book), so for the most part, there's not too much trouble flipping around with the maps. I mean, occasionally you might have to flip back and forth a couple pages to find the map you're looking for, but for the most part the publishers do a very good job of putting the maps right where you need them in the main text.

Plans for Further Reading

Lives of the Noble Greeks and Romans by Plutarch (W)

I've mentioned that I'm much more interested in the biographies of the personalities behind this war rather than the military history itself. Which means I really need to get around to reading Plutarch's Lives of the Noble Greeks and Romans. Many of the Greek lives in Plutarch are actually from the Peloponnesian War: Pericles, Alcibiades, Cimon, Nicias, Lysander, etc.

As always finding books in Vietnam is difficult, but Plutarch is actually available on Project Gutenberg, and I bought a kindle last year precisely for this kind of thing. So I hope to read it this year.

(I mentioned back in 2018 that I wanted to read Plutarch, but I was worried that I didn't have the background to understand the Greek half of his biographies. But now that I've read Herodotus, and I've read about the Peloponnesian War, I think I've got enough background to tackle Plutarch.)

History of the Peloponnesian War by Thucydides (W)

Alright, so now that I've finished this book, I guess there's no excuse not to tackle Thucydides next. Except unlike Plutarch, I'm not going to try to read Thucydides off of Project Gutenberg. I get the impression this is a book that you really need to have a proper edition with the maps and the footnotes and everything. So I'm probably going to have to wait around until I'm back in the United States before I can track down a copy. And who knows when that will next be? But whenever that happens, Thucydides is on the list. I will buy a copy when I'm next back in the U.S.

Re-read: The Peloponnesian War by Donald Kagan

When I do get around to Thucydides, whenever that ends up being, I suspect I'll want to re-read this book. People say it's a really good companion book to read while you're reading Thucydides, and it will no doubt have faded in my mind in a couple years. So I'm either going to have to save my copy, or else track down another copy in the future.

There are, as I indicated above, any number of Greek plays that are directly or indirectly about The Peloponnesian War. But these two are the ones I'm most interested in. And then maybe I'll get around to reading others after that.

So far I've only listened to a few episodes regarding the Peloponnesian War. But it's good enough that I think I want to listen to the whole thing. At some point. (It'll be a while before I finish Revolutions podcast obviously.) And I guess I'll just take the position that the allegations of harassments against Ryan Stitt don't affect the contents of the podcast.

The Cartoon History of the Universe (W)

I mentioned above that this was the comic book that got me into this whole time period to begin with. But I never actually read it cover-to-cover. I just flipped through it in the library one day. Now that I've started reading and reviewing comic books on this blog, I should really read this one day.

Who knows when I'll ever be able to track down a copy. But someday I'll get around to it.

Links

The fifth-century BC war between Athens and Sparta is one of those conflicts that’s always ripe for retelling, but it’s big and daunting and there’s always new research to take into account (and for all his faults, Thucydides is a bit of a tough act to follow). In other words, there’s a grave potential when reading a new history of the Peloponnesian War to hit icebergs of boredom calved off glaciers of caution, but that doesn’t happen in Kagan’s fantastic account: he keeps the story’s several parallel theaters active and interesting, and he manages to write about the whole conflict with tremendous freshness.

It's tough to rate a book like this. I feel like Donald Kagan did the best he could with the material that he had. So maybe I should give him 10 out of 10 on effort. On the other hand, I give these ratings out on how enjoyable the book was for me personally to read. And parts of this book did feel like a slog at times going through all the different military campaigns. So maybe 7 out of 10?

But then, even when it was slogging through the military history, it was always readable. The prose was clear. The maps were easy to follow. Final verdict: 8 out of 10

November 13, 2022 The Peloponnesian War p.1-96

November 20, 2022 The Peloponnesian War p.96-162

November 27, 2022 The Peloponnesian War p.162-172

December 4, 2022 The Peloponnesian War p.172-224

December 11, 2022 The Peloponnesian War p.224-292

December 18, 2022 The Peloponnesian War p.292-352

December 23, 2022 The Peloponnesian War p.352-396

January 1, 2023 The Peloponnesian War p.396-494

Video Review (Playlist HERE)

No comments:

Post a Comment